Benchmarking GPUs: Measuring Throughput between CPU and GPU

- Steve Scargall

- How to

- August 16, 2024

This article was inspired by a LinkedIn post by Dennis Kennetz . The CPU to GPU bandwidth check is available on GitHub which uses a specific flow to assess the data transfer rates. Like many in the industry, my focus is on AI and ML workloads and how we can improve efficiencies and performance using DRAM, CXL, CPU, GPUs, and software improvements.

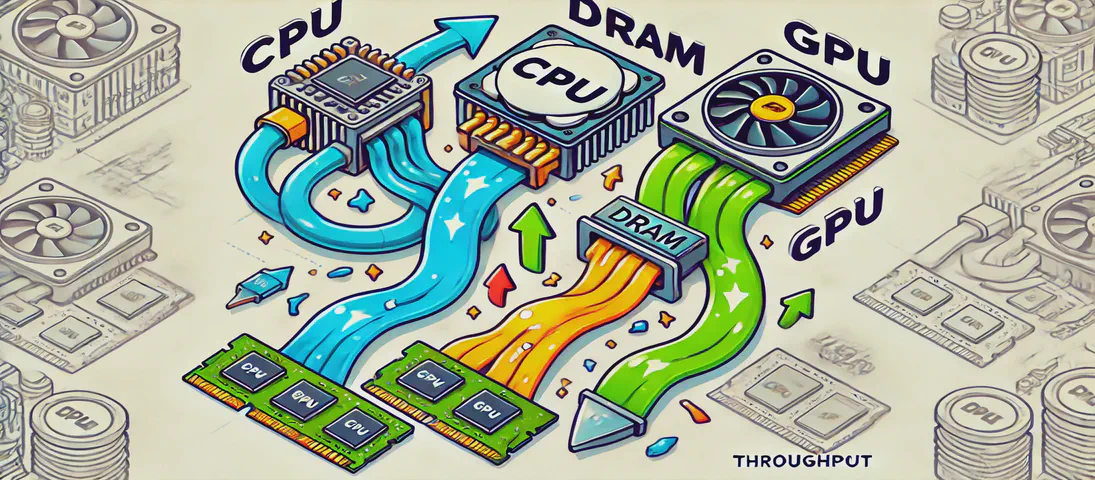

In the rapidly evolving landscape of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML), the ability to process vast amounts of data efficiently is paramount. As AI models grow in complexity and size, the demand for high-performance computing resources intensifies. At the heart of this demand lies the crucial task of optimizing data transfers between various components of a computing system, particularly from DRAM, CPU, and emerging technologies like CXL (Compute Express Link) to and from the GPU.

Benchmarking these data transfers is not just a technical exercise; it’s a strategic necessity. The GPU, renowned for its parallel processing capabilities, is the workhorse of AI and ML workloads. However, its performance is often bottlenecked by the speed and efficiency of data movement. Understanding and optimizing these data pathways can lead to significant improvements in model training times, inference speeds, and overall system efficiency.

As DRAM continues to provide the backbone for high-capacity memory needs, and CXL emerges as a game-changer with its ability to offer scalable and flexible memory solutions, the landscape of memory technology is set to transform. Benchmarking the data transfer capabilities of these technologies in conjunction with the CPU and GPU is essential for harnessing their full potential. By doing so, developers and engineers can ensure that AI and ML workloads are not only faster but also more efficient and cost-effective.

Since I spend a lot of time architecting software and systems, then testing and benchmarking them, I wanted to write up how I improved Dennis’ benchmark tool and how I use Bandwidth Check and NVidia’s nvbandwidth benchmark to characterise GPU performance.

Benchmarking Data Transfer with Bandwidth_Check

Bandwidth Check follows these steps to measure the throughput:

Allocate Host Data: Begin by allocating a large array of host data. An array of approximately 1 million

float32values is used. This size is chosen to ensure that the data transfer is substantial enough to provide meaningful results.Populate the Host Array: Fill the host array with values. This step is necessary to simulate real-world scenarios where data is being transferred from the CPU to the GPU for processing.

Allocate Device Data: Allocate memory on the GPU (device) to hold the data. The size of this allocation should match the host data size.

Create CUDA Events: Use CUDA events to measure the time taken for the data transfer. Create a start and stop event to record the timing.

Record Start Event and Transfer Data: Record the start event and perform 1000 copies of the 1 million floats from the CPU to the GPU. This repeated transfer helps average out any anomalies and provides a stable measurement of throughput.

Record Stop Event: After the transfers, record the stop event.

Calculate Transfer Time: Calculate the time taken for the data transfers by measuring the difference between the start and stop events. This time can then be used to calculate the throughput.

Obtaining GPU Model and PCIe Information

To better understand the performance characteristics and results from any benchmark tool, it’s useful to know the hardware layout, design, and expected performance characteristics first. In this case, I’m interested in the CPU, GPU, DRAM, and CXL device performance.

- Get GPU Model: Use the command

nvidia-smi --list-gpusto list all GPUs in the system along with their models. This information is crucial for understanding the capabilities and limitations of your GPU. For example:

$ nvidia-smi --list-gpus

GPU 0: NVIDIA A10 (UUID: GPU-93f1c83e-8fe0-8e60-b528-f67bab501449)

This NVidia A10 GPU is a PCIe Gen4 64GB/s device.

- Get PCIe Lanes Info: Use the

lspcicommand to obtain details about the PCIe lanes used by the GPU. This can be done by running to provide detailed information about the PCIe configuration.

$ lspci | grep -i nvidia

99:00.0 3D controller: NVIDIA Corporation GA102GL [A10] (rev a1)

$ sudo lspci -s 99:00.0 -vvv

99:00.0 3D controller: NVIDIA Corporation GA102GL [A10] (rev a1)

Subsystem: NVIDIA Corporation GA102GL [A10]

Physical Slot: 1

Control: I/O- Mem+ BusMaster+ SpecCycle- MemWINV- VGASnoop- ParErr+ Stepping- SERR+ FastB2B- DisINTx+

Status: Cap+ 66MHz- UDF- FastB2B- ParErr- DEVSEL=fast >TAbort- <TAbort- <MAbort- >SERR- <PERR- INTx-

Latency: 0

Interrupt: pin A routed to IRQ 16

NUMA node: 1

Region 0: Memory at d8000000 (32-bit, non-prefetchable) [size=16M]

Region 1: Memory at 222000000000 (64-bit, prefetchable) [size=32G]

Region 3: Memory at 223840000000 (64-bit, prefetchable) [size=32M]

Capabilities: [60] Power Management version 3

Flags: PMEClk- DSI- D1- D2- AuxCurrent=0mA PME(D0+,D1-,D2-,D3hot+,D3cold-)

Status: D0 NoSoftRst+ PME-Enable- DSel=0 DScale=0 PME-

Capabilities: [68] Null

Capabilities: [78] Express (v2) Endpoint, MSI 00

DevCap: MaxPayload 256 bytes, PhantFunc 0, Latency L0s unlimited, L1 <64us

ExtTag+ AttnBtn- AttnInd- PwrInd- RBE+ FLReset+ SlotPowerLimit 75.000W

DevCtl: CorrErr- NonFatalErr- FatalErr+ UnsupReq-

RlxdOrd+ ExtTag+ PhantFunc- AuxPwr- NoSnoop+ FLReset-

MaxPayload 256 bytes, MaxReadReq 512 bytes

DevSta: CorrErr- NonFatalErr- FatalErr- UnsupReq- AuxPwr- TransPend-

LnkCap: Port #0, Speed 16GT/s, Width x16, ASPM not supported

ClockPM+ Surprise- LLActRep- BwNot- ASPMOptComp+

[...snip...]

Kernel driver in use: nvidia

Kernel modules: nvidiafb, nouveau, nvidia_drm, nvidia

This is a lot of information to understand. The key parts to look at are the Slot number Physical Slot: 1 and number of PCIe lanes used LnkCap: Port #0, Speed 16GT/s, Width x16, ASPM not supported, which confirms Slot 1 is a PCIe Gen4 (16GT/s) x16 slot.

- Get the CXL Info: Using the

lspcicommand, we can get the CXL device information:

$ lspci | grep -i cxl

ab:00.0 CXL: Micron Technology Inc Device 6400 (rev 01)

$ sudo lspci -s ab:00.0 -vvv

ab:00.0 CXL: Micron Technology Inc Device 6400 (rev 01) (prog-if 10 [CXL Memory Device (CXL 2.x)])

Subsystem: Micron Technology Inc Device 0501

Control: I/O- Mem+ BusMaster+ SpecCycle- MemWINV- VGASnoop- ParErr+ Stepping- SERR+ FastB2B- DisINTx+

Status: Cap+ 66MHz- UDF- FastB2B- ParErr- DEVSEL=fast >TAbort- <TAbort- <MAbort- >SERR- <PERR- INTx-

Latency: 0, Cache Line Size: 64 bytes

NUMA node: 1

[...snip...]

Kernel driver in use: cxl_pci

Kernel modules: cxl_pci

For reference, this is a x8 PCIe Gen5 device.

Calculating PCIe Theoretical Throughput

I previously wrote a PCIe Speeds and Feeds article explaining how the PCIe generations line up to theoretical throughput and how to calculate it. In the article, you’ll see that a x16 Gen4 slot has a theoretical 64GB/sec bi-directional bandwidth.

Understanding Bandwidth vs Throughput/Effective Bandwidth

Bandwidth and throughput, also called ‘Effective Bandwidth’, are two important concepts in that are often incorrectly used interchangably, but they have distinct meanings:

Bandwidth refers to the maximum capacity of a channel to carry data. It is a theoretical measure of how much data can be transmitted over a link in a given amount of time, typically expressed in bits per second (bps). Bandwidth is akin to the width of a highway, indicating the potential number of vehicles (data packets) that can travel simultaneously.

Throughput/Effective Bandwidth, on the other hand, is the actual rate at which data is successfully transferred over the network. It is a practical measure, reflecting the real-world performance of a device over a link, and is often lower than the bandwidth due to factors such as the application, device/link congestion, latency, and protocol overhead. Throughput is analogous to the actual speed of traffic flow on the highway, which may be affected by traffic jams or road conditions.

Understanding the difference between these two metrics is crucial for optimizing performance, as high bandwidth does not necessarily guarantee high throughput.

Building the Bandwidth_Check Benchmark

The Benchmark shource code requires the following prerequisites:

- GCC

- NVidia nvcc

Follow the NVIDIA CUDA Installation Guide for Linux to ensure your environment is configured correctly.

Building the source code is trivial:

~/cuda_examples/003_bandwidth_check$ make

nvcc -x cu -O3 -std=c++11 -arch=sm_86 -I/usr/local/cuda-12.3/bin/../include ./bandwidth_check.cu -o main -L/usr/local/cuda-12.3/bin/../lib64

You should see a new main binary in the same directory which is the benchmark.

Running the Benchmark

Since my A10 GPU is on a PCIe slot for CPU Socket 1 (NUMA node: 1 fromthe lspci output above), I used ndctl to ensure the benchmark runs on Socket1 using memory from Socket1 to avoid cross socket communication that will impact the results. I ran the benchmark several times to look for consistencies. The first result is slower than the rest, likely due to page faults.

$ for f in {1..10}; do numactl --cpunodebind=1 --membind=1 ./main; done

Bandwidth: 14.857154 GB/s

Bandwidth: 18.323864 GB/s

Bandwidth: 19.694246 GB/s

Bandwidth: 19.409304 GB/s

Bandwidth: 18.445518 GB/s

Bandwidth: 19.691296 GB/s

Bandwidth: 19.410233 GB/s

Bandwidth: 19.578987 GB/s

Bandwidth: 19.683897 GB/s

Bandwidth: 19.635284 GB/s

As a reminder, this is a unidirectional memory copy from the CPU to the GPU, so the theoretical throughput should be 32GB/sec.

It was rather disappointing to get only 20GB/sec, so I did a quick sanity check on the system:

- NVidia Toolkit 12.6 (latest at the time of testing)

- The NVidia Driver is current (550.54.15)

- The NVidia A10 is in a x16 slot

- The NVidia A10 power is not limited (

nvidia-smi -q -d POWERshowsMax Power Limit: 150.00 W, which is correct) - The Linux Kernel is recent (6.5.0-21)

- DRAM per socket is ~300GB/s as measured by Intel MLC (8 x DDR5-4800 == 38.4 x 8 == 307GB/sec)

- Verified the GPU NUMA Topology using

nvidia-smi topo -mis connected to Socket 1 - Linux CPU Scaling Governor is set to ‘performance’. See How To Set Linux CPU Scaling Governor to Max Performance

I then read the NVidia CUDA Best Practices documentation. Reviewing the code showed several areas for improvement:

- Single-threaded Execution: The code is single-threaded and uses a single CUDA stream to perform data transfers. While this is a common approach, it may not fully utilize the available bandwidth of PCIe Gen4.

- Asynchronous Transfers: The code uses cudaMemcpyAsync for asynchronous data transfers, which is good for overlapping computation and communication. However, since the code waits for the stream to synchronize after recording the stop event, it effectively serializes the transfer operations, which might not fully leverage the potential parallelism.

- Memory Allocation: The host memory is allocated using standard dynamic memory allocation, which may not be page-locked (pinned). Using pinned memory can significantly increase transfer rates because it allows for faster data transfers between the host and device.

- No Warmup: Data is immediately allocated and used. Benchmarks typically perform some operations before measurements start to avoid page faults on first use, which can impact the results.

I modified the code to include these observations, and got 25GB/s, which is close to my expectation. We’re not going to get 32GB/sec, but this is “close enough”.

$ for f in {1..10}; do numactl --cpunodebind=1 --membind=1 ./main -i 2000 -s 8 -w 5; done

Bandwidth: 25.149124 GB/s

Bandwidth: 25.151405 GB/s

Bandwidth: 25.150078 GB/s

Bandwidth: 25.150782 GB/s

Bandwidth: 25.147242 GB/s

Bandwidth: 25.148067 GB/s

Bandwidth: 25.147434 GB/s

Bandwidth: 25.147575 GB/s

Bandwidth: 25.147165 GB/s

Bandwidth: 25.146469 GB/s

Note: This is the same result I get from the NVidia nvbandwidth benchmark , which gives me confidence my changes were along the right lines.

$ ./nvbandwidth -t host_to_device_memcpy_ce

nvbandwidth Version: v0.5

Built from Git version: v0.5-1-g4da7d7e

NOTE: This tool reports current measured bandwidth on your system.

Additional system-specific tuning may be required to achieve maximal peak bandwidth.

CUDA Runtime Version: 12040

CUDA Driver Version: 12040

Driver Version: 550.54.15

Device 0: NVIDIA A10

Running host_to_device_memcpy_ce.

memcpy CE CPU(row) -> GPU(column) bandwidth (GB/s)

0

0 25.17

SUM host_to_device_memcpy_ce 25.17

$ ./nvbandwidth -t host_to_device_memcpy_sm

nvbandwidth Version: v0.5

Built from Git version: v0.5-1-g4da7d7e

NOTE: This tool reports current measured bandwidth on your system.

Additional system-specific tuning may be required to achieve maximal peak bandwidth.

CUDA Runtime Version: 12040

CUDA Driver Version: 12040

Driver Version: 550.54.15

Device 0: NVIDIA A10

Running host_to_device_memcpy_sm.

memcpy SM CPU(row) -> GPU(column) bandwidth (GB/s)

0

0 25.25

SUM host_to_device_memcpy_sm 25.25

Measuring Remote Memory Throughput

Since this is a 2-Socket server, we can use numactl to use memory from the remote socket, which forces the data over the CPU interconnect (UPI on Intel). Although the latency of the remote memory is higher than local memory, the high bandwidth UPI interface shouldn’t be a problem given this is a single GPU. Indeed, the results confirm this:

$ for f in {1..10}; do numactl --cpunodebind=1 --membind=0 ./main; done

Bandwidth: 25.131380 GB/s

Bandwidth: 25.128679 GB/s

Bandwidth: 25.127956 GB/s

Bandwidth: 25.127678 GB/s

Bandwidth: 25.128275 GB/s

Bandwidth: 25.128101 GB/s

Bandwidth: 25.127754 GB/s

Bandwidth: 25.128149 GB/s

Bandwidth: 25.127687 GB/s

Bandwidth: 25.128853 GB/s

Measuring CXL to GPU

Compute Express Link (CXL) memory is attached to the PCIe bus and uses a lower-overhead CXL protocol. CXL Memory devices can expand the DRAM capacity and bandwidth. CXL devices have higher latency than DRAM as they are physically further away from the CPU. In the following example, a CXL memory device is attached to Socket 1. Since a CXL Memory device has no CPUs, they appear as cpu-less or memory-only NUMA Nodes:

$ numactl -H

available: 3 nodes (0-2)

node 0 cpus: 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95

node 0 size: 515714 MB

node 0 free: 353710 MB

node 1 cpus: 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 119 120 121 122 123 124 125 126 127

node 1 size: 516020 MB

node 1 free: 385295 MB

node 2 cpus:

node 2 size: 131072 MB <== CXL

node 2 free: 121990 MB

node distances:

node 0 1 2

0: 10 21 24 <== DRAM

1: 21 10 14 <== DRAM

2: 24 14 10 <== CXL

Running the benchmark shows this device is almost as fast as DRAM. I measured the throughput of this CXL device at ~25GB/sec for read and write operations, so it’s capable of saturating the A10 GPU, which makes these results quite impressive.

$ for f in {1..10}; do numactl --cpunodebind=1 --membind=2 ./main -i 2000 -s 8 -w 5; done

Bandwidth: 25.132347 GB/s

Bandwidth: 25.137192 GB/s

Bandwidth: 24.996754 GB/s

Bandwidth: 24.859182 GB/s

Bandwidth: 24.790831 GB/s

Bandwidth: 24.311480 GB/s

Bandwidth: 24.019766 GB/s

Bandwidth: 24.894602 GB/s

Bandwidth: 25.099909 GB/s

Bandwidth: 23.612177 GB/s

Using NVidia’s NSight

I wanted to see if there was anything left on the table that would improve the result further. NVidia’s Nsight Systems provides a comprehensive view of how your application utilizes CPU and GPU resources, which can help identify bottlenecks.

Using the nsys profile command, we can collect detailed profiling information when the benchmark runs a single iteration:

$ sudo nsys profile --trace=cuda -o report-nsys ./main

Bandwidth: 25.088665 GB/s

Generating '/tmp/nsys-report-9f23.qdstrm'

[1/1] [========================100%] nsys-report-5466.nsys-rep

Generated:

/tmp/nsys-report-5466.nsys-rep

Now we can analyze the report (/tmp/nsys-report-5466.nsys-rep).

To open the report in the GUI, use:

nsys-ui /tmp/nsys-report-5466.nsys-rep

To view a summary in the command line, use:

nsys stats /tmp/nsys-report-5466.nsys-rep

Using the CLI, I see the following:

Processing [/tmp/nsys-report-5466.sqlite] with [/opt/nvidia/nsight-systems/2024.4.2/host-linux-x64/reports/cuda_api_sum.py]...

** CUDA API Summary (cuda_api_sum):

Time (%) Total Time (ns) Num Calls Avg (ns) Med (ns) Min (ns) Max (ns) StdDev (ns) Name

-------- --------------- --------- ------------- ------------- ----------- ----------- ------------- ----------------------

93.5 2,698,833,019 8 337,354,127.4 336,983,831.0 5,349,666 668,729,737 353,506,113.1 cudaStreamSynchronize

6.0 174,571,091 1 174,571,091.0 174,571,091.0 174,571,091 174,571,091 0.0 cudaHostAlloc

0.3 9,584,641 1 9,584,641.0 9,584,641.0 9,584,641 9,584,641 0.0 cudaFreeHost

0.1 2,631,431 1,010 2,605.4 2,488.0 2,399 26,611 1,067.2 cudaMemcpyAsync

0.0 174,753 1 174,753.0 174,753.0 174,753 174,753 0.0 cudaFree

0.0 135,973 1 135,973.0 135,973.0 135,973 135,973 0.0 cudaMalloc

0.0 45,262 4 11,315.5 2,304.5 1,919 38,734 18,282.6 cudaStreamCreate

0.0 22,386 2 11,193.0 11,193.0 742 21,644 14,779.9 cudaEventCreate

0.0 14,663 4 3,665.8 2,018.0 1,667 8,960 3,533.6 cudaStreamDestroy

0.0 14,308 2 7,154.0 7,154.0 6,983 7,325 241.8 cudaEventRecord

0.0 2,959 1 2,959.0 2,959.0 2,959 2,959 0.0 cudaEventSynchronize

0.0 1,775 2 887.5 887.5 415 1,360 668.2 cudaEventDestroy

0.0 1,441 1 1,441.0 1,441.0 1,441 1,441 0.0 cuModuleGetLoadingMode

Processing [/tmp/nsys-report-5466.sqlite] with [/opt/nvidia/nsight-systems/2024.4.2/host-linux-x64/reports/cuda_gpu_mem_time_sum.py]...

** CUDA GPU MemOps Summary (by Time) (cuda_gpu_mem_time_sum):

Time (%) Total Time (ns) Count Avg (ns) Med (ns) Min (ns) Max (ns) StdDev (ns) Operation

-------- --------------- ----- ----------- ----------- --------- --------- ----------- ----------------------------

100.0 2,700,179,270 1,010 2,673,444.8 2,673,361.0 2,672,688 2,682,673 477.6 [CUDA memcpy Host-to-Device]

Processing [/tmp/nsys-report-5466.sqlite] with [/opt/nvidia/nsight-systems/2024.4.2/host-linux-x64/reports/cuda_gpu_mem_size_sum.py]...

** CUDA GPU MemOps Summary (by Size) (cuda_gpu_mem_size_sum):

Total (MB) Count Avg (MB) Med (MB) Min (MB) Max (MB) StdDev (MB) Operation

---------- ----- -------- -------- -------- -------- ----------- ----------------------------

67,779.953 1,010 67.109 67.109 67.109 67.109 0.000 [CUDA memcpy Host-to-Device]

To understand each section of the report, refer to the documentation .

From the API summary, we see 93.5% of the time is spent in cudaStreamSynchronize(). This is explained in the NVidia CUDA ‘Using CPU Timers

’ documentation.

8.1.1. Using CPU Timers Any CPU timer can be used to measure the elapsed time of a CUDA call or kernel execution. The details of various CPU timing approaches are outside the scope of this document, but developers should always be aware of the resolution their timing calls provide.

When using CPU timers, it is critical to remember that many CUDA API functions are asynchronous; that is, they return control back to the calling CPU thread prior to completing their work. All kernel launches are asynchronous, as are memory-copy functions with the Async suffix on their names. Therefore, to accurately measure the elapsed time for a particular call or sequence of CUDA calls, it is necessary to synchronize the CPU thread with the GPU by calling cudaDeviceSynchronize() immediately before starting and stopping the CPU timer. cudaDeviceSynchronize()blocks the calling CPU thread until all CUDA calls previously issued by the thread are completed.

Although it is also possible to synchronize the CPU thread with a particular stream or event on the GPU, these synchronization functions are not suitable for timing code in streams other than the default stream. cudaStreamSynchronize() blocks the CPU thread until all CUDA calls previously issued into the given stream have completed. cudaEventSynchronize() blocks until a given event in a particular stream has been recorded by the GPU. Because the driver may interleave execution of CUDA calls from other non-default streams, calls in other streams may be included in the timing.

Because the default stream, stream 0, exhibits serializing behavior for work on the device (an operation in the default stream can begin only after all preceding calls in any stream have completed; and no subsequent operation in any stream can begin until it finishes), these functions can be used reliably for timing in the default stream.

Be aware that CPU-to-GPU synchronization points such as those mentioned in this section imply a stall in the GPU’s processing pipeline and should thus be used sparingly to minimize their performance impact.

Unfortunately, it doesnt’t look like any additional code changes would improve the results shown above. I achieved the best I could hope for.

Conclusion

The importance of optimizing data transfer throughput between CPU and GPU extends beyond traditional computing applications and is particularly critical in the realms of AI and Machine Learning. As these fields continue to evolve, the demand for high-capacity and high-bandwidth memory solutions becomes increasingly pronounced. The integration of advanced memory technologies like DRAM and CXL (Compute Express Link) is pivotal in addressing these demands.

In AI and ML workloads, the size of models and datasets is rapidly expanding, necessitating memory solutions that can handle vast amounts of data efficiently. DRAM continues to play a crucial role by providing the necessary capacity and bandwidth, but it faces challenges such as latency and power consumption. CXL emerges as a promising technology that can complement DRAM by enabling memory pooling and expansion, thus enhancing the overall memory footprint and bandwidth available to AI applications. This is particularly beneficial for data-intensive tasks, where the ability to access large memory pools in real-time can significantly enhance performance.

CXL’s architecture allows for more flexible and scalable memory configurations, which can be crucial for AI systems that require dynamic resource allocation. By abstracting the memory type from the processor, CXL facilitates the integration of new memory technologies, potentially leading to more efficient and cost-effective AI infrastructures.

In conclusion, as AI and ML continue to push the boundaries of computing, the role of memory technologies like DRAM and CXL becomes increasingly vital. These technologies not only support the growing capacity and bandwidth needs but also pave the way for innovative solutions that can sustain the rapid pace of AI advancements. For developers and engineers, understanding and leveraging these memory technologies is key to unlocking the full potential of AI systems, ensuring they can deliver faster, more accurate, and more reliable results.